Student Missions

Mission 1: Itty Bitty Things.

Mission Objectives: You should be able to...

1. Describe the structure of an atom.

2. Describe how radioisotopes are used in medicine.

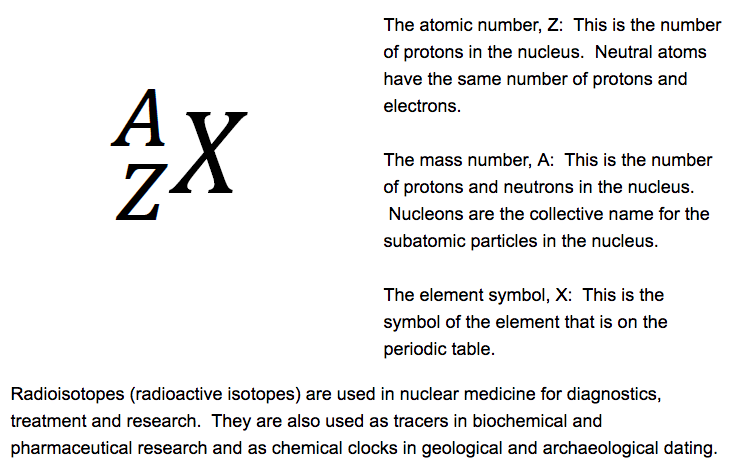

All neutral atoms contain the same number of protons & electrons. The number of protons determines the element's identity. For instance, 8 protons = oxygen. 17 protons = chlorine. 20 protons = calcium. This does not change.

Electrons determine chemical behavior. Valence electrons (electrons in the outermost energy levels) are significant in this regard, because the number of valence electrons determine how an element behaves in certain conditions. Elements with an octet (8 valence electrons) are unusually stable and do not combine to form compounds (noble gases have an octet, with the exception of helium).

Neutrons determine isotopes. They do not affect the charge or the element's identity. However, they do affect the mass of the nucleus. Several elements have multiple isotopes. Almost every element has isotopes, and what is represented on the periodic table is an average of all of the isotopes of a particular element (which is why the atomic mass is a decimal). In a later mission, you will learn how to use mass spectrum data to calculate relative atomic mass (RAM).

This is basic structural information about the atom; what we know for sure. We also suspect something else: that subatomic particles are made up of quarks and all particles have anti-particles that, when they collide, release energy in the form of gamma rays.

Mr. Andrew Weng breaks down the entirety of section 2.1. He's not the most exciting lecturer, but he's comprehensive.

Mission 1: Itty Bitty Things.

Mission Objectives: You should be able to...

1. Describe the structure of an atom.

2. Describe how radioisotopes are used in medicine.

All neutral atoms contain the same number of protons & electrons. The number of protons determines the element's identity. For instance, 8 protons = oxygen. 17 protons = chlorine. 20 protons = calcium. This does not change.

Electrons determine chemical behavior. Valence electrons (electrons in the outermost energy levels) are significant in this regard, because the number of valence electrons determine how an element behaves in certain conditions. Elements with an octet (8 valence electrons) are unusually stable and do not combine to form compounds (noble gases have an octet, with the exception of helium).

Neutrons determine isotopes. They do not affect the charge or the element's identity. However, they do affect the mass of the nucleus. Several elements have multiple isotopes. Almost every element has isotopes, and what is represented on the periodic table is an average of all of the isotopes of a particular element (which is why the atomic mass is a decimal). In a later mission, you will learn how to use mass spectrum data to calculate relative atomic mass (RAM).

This is basic structural information about the atom; what we know for sure. We also suspect something else: that subatomic particles are made up of quarks and all particles have anti-particles that, when they collide, release energy in the form of gamma rays.

Mr. Andrew Weng breaks down the entirety of section 2.1. He's not the most exciting lecturer, but he's comprehensive.

Mission 2: Back That Mass Up!!!

Mission Objectives: You should be able to...

1. Define "relative atomic mass".

2. Explain how a mass spectrometer works.

Relative atomic mass is defined as the ratio of the average mass of an atom to the unified atomic mass unit (1 amu). The book defines 1 amu as 1.6605402 * 10^-27.

Mass spectrometers are designed to determine the relative atomic masses of elements. There are five stages in the process: vaporization, ionization, acceleration, deflection and detection. Samples are heated and vaporized to produce gaseous atoms and molecules and then bombarded by high energy electrons, generating positively charged species. The positive ions are accelerated into an electric field and deflected by a magnetic field that is perpendicular to their path (recall the video).

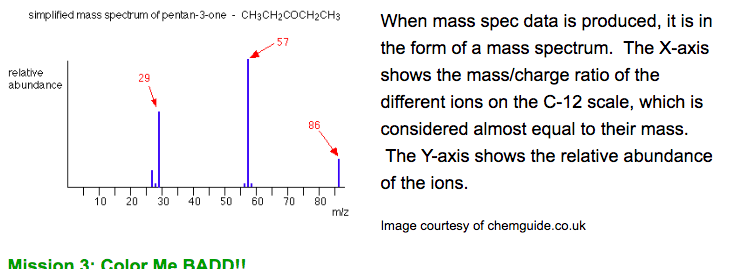

The degree of deflection depends on the mass to charge ratio (m/Z). The species with the smallest mass (m) and highest charge (Z) will be deflected the most. Particles with no charge are not deflected. The detector then detects species of a particular m/z ratio. The ions hit the counter and the electric signal is detected. It is a plot of relative abundance (of each isotope) versus mass number (A). Peak height indicates the relative abundance of the isotope.

Below you will find two videos about mass spectrometry. The first video describes how a mass spec works and the second video, from Paul Anderson of Bozeman Science, goes into detail about mass spectrometry. We will start the Anderson video at 1:45, unless you want to hear about John Dalton's contributions to chemistry (we will get to this shortly).

Mission Objectives: You should be able to...

1. Define "relative atomic mass".

2. Explain how a mass spectrometer works.

Relative atomic mass is defined as the ratio of the average mass of an atom to the unified atomic mass unit (1 amu). The book defines 1 amu as 1.6605402 * 10^-27.

Mass spectrometers are designed to determine the relative atomic masses of elements. There are five stages in the process: vaporization, ionization, acceleration, deflection and detection. Samples are heated and vaporized to produce gaseous atoms and molecules and then bombarded by high energy electrons, generating positively charged species. The positive ions are accelerated into an electric field and deflected by a magnetic field that is perpendicular to their path (recall the video).

The degree of deflection depends on the mass to charge ratio (m/Z). The species with the smallest mass (m) and highest charge (Z) will be deflected the most. Particles with no charge are not deflected. The detector then detects species of a particular m/z ratio. The ions hit the counter and the electric signal is detected. It is a plot of relative abundance (of each isotope) versus mass number (A). Peak height indicates the relative abundance of the isotope.

Below you will find two videos about mass spectrometry. The first video describes how a mass spec works and the second video, from Paul Anderson of Bozeman Science, goes into detail about mass spectrometry. We will start the Anderson video at 1:45, unless you want to hear about John Dalton's contributions to chemistry (we will get to this shortly).

Mission 3: Color Me BADD!!

Mission Objectives. You should be able to...

1. Explain the phenomenon of emission spectra.

2. Describe the line emission spectrum of hydrogen and its relationship to the Bohr Model.

3. Determine how an atom is structured based on its energy level(s).

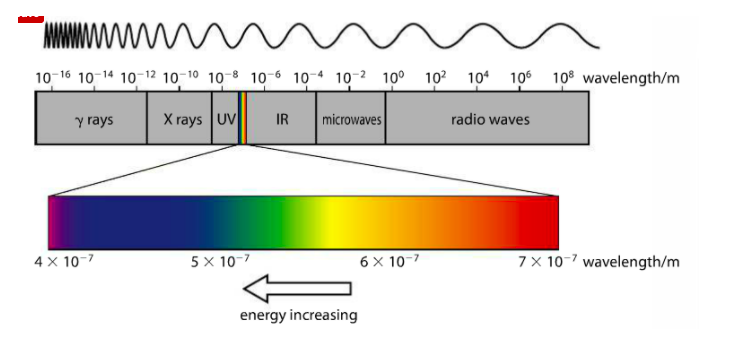

The electromagnetic spectrum is a visualization of electromagnetic radiation. It ranges from low energy radio waves to high energy gamma rays. Energy is inversely proportional to wavelength. High energy radiation has very small wavelengths and low energy radiation have very long wavelengths. SI unit for energy is the joule (J), wavelength is measured in meters (m), and frequency is measured in hertz (Hz). All eMag waves travel at the same speed (c) but are distinguished by their different wavelengths (greek letter lambda). Different colors of visible light (the sliver of the spectrum we can see) have different wavelengths. There is a full eMag spectrum in your Data Booklet.

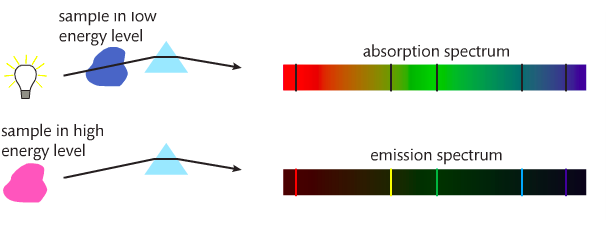

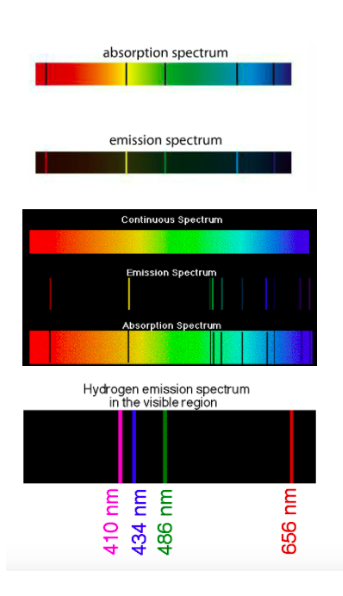

When white light is heated and/or passed through a prism, a continuous spectrum is produced. If a pure gaseous element is subjected to an electrical discharge, the gas emits radiation. The result is an emission spectrum.

If a cloud of cold gas is placed between a hot metal and a detector, an absorption spectrum is produced. The gaseous atoms absorb certain wavelengths (which show up on the emission spectrum). See below.

Absorption and emission spectra are used in astronomy to analyze star light.

Mission Objectives. You should be able to...

1. Explain the phenomenon of emission spectra.

2. Describe the line emission spectrum of hydrogen and its relationship to the Bohr Model.

3. Determine how an atom is structured based on its energy level(s).

The electromagnetic spectrum is a visualization of electromagnetic radiation. It ranges from low energy radio waves to high energy gamma rays. Energy is inversely proportional to wavelength. High energy radiation has very small wavelengths and low energy radiation have very long wavelengths. SI unit for energy is the joule (J), wavelength is measured in meters (m), and frequency is measured in hertz (Hz). All eMag waves travel at the same speed (c) but are distinguished by their different wavelengths (greek letter lambda). Different colors of visible light (the sliver of the spectrum we can see) have different wavelengths. There is a full eMag spectrum in your Data Booklet.

When white light is heated and/or passed through a prism, a continuous spectrum is produced. If a pure gaseous element is subjected to an electrical discharge, the gas emits radiation. The result is an emission spectrum.

If a cloud of cold gas is placed between a hot metal and a detector, an absorption spectrum is produced. The gaseous atoms absorb certain wavelengths (which show up on the emission spectrum). See below.

Absorption and emission spectra are used in astronomy to analyze star light.

The lines in an emission spectrum have specific wavelengths. Each corresponds to a discrete amount of energy. This is called quantization. A photon (discrete packet of light) is a quantum of radiation and relates wavelength and energy. Look at the relationship between speed of light and Planck's constant (page 52). As a result, Bohr used this information to describe electron behavior in the hydrogen atom. The electron orbits the nucleus the same way planets orbit the sun (hence the name "planetary model"). The acceleration of the electron moving at high velocity keeps it in orbit. Each orbit has a definite energy associated with it: the energy of the orbiting electron is quantized.

When an electron is in the ground state and becomes excited, it absorbs energy and jumps to a higher level. When the electron falls back down to a lower energy level, it releases energy in the form of light (a photon). The photon corresponds to a particular wavelength.

Bohr's model works only for hydrogen. The reason it doesn't work for other elements is because (1) it assumes that the positions of the electrons are fixed, (2) it assumes that energy levels are circular, and (3) it suggests an incorrect size scale for atoms.

When an electron is in the ground state and becomes excited, it absorbs energy and jumps to a higher level. When the electron falls back down to a lower energy level, it releases energy in the form of light (a photon). The photon corresponds to a particular wavelength.

Bohr's model works only for hydrogen. The reason it doesn't work for other elements is because (1) it assumes that the positions of the electrons are fixed, (2) it assumes that energy levels are circular, and (3) it suggests an incorrect size scale for atoms.

The above image from the Pearson text (p. 71) shows the changing wavelength of the eMag spectrum in meters (m). On the left side, we have high energy gamma waves, which have the shortest wavelengths, and on the right side, we have radio waves, which have the longest wavelengths. The sliver of color between UV and IR is what our eye sees, magnified as the bar of color directly above.

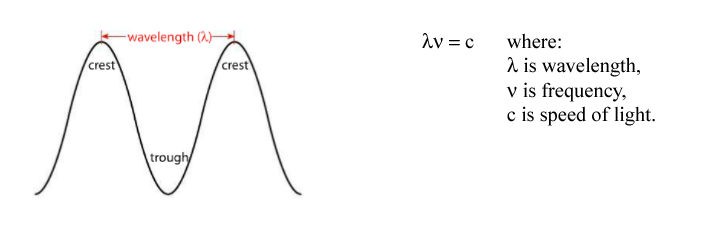

Wavelength is measured from the crest (or trough) of one wave to the crest (or trough) of another. The number of waves that pass a given point at any time is called frequency. The relationship between frequency and wavelength is inverse: the shorter the wavelength, the higher the frequency.

Wavelength is measured from the crest (or trough) of one wave to the crest (or trough) of another. The number of waves that pass a given point at any time is called frequency. The relationship between frequency and wavelength is inverse: the shorter the wavelength, the higher the frequency.

|

When eMag radiation is passed through atoms, some of the radiation is absorbed and used to excite the atoms from low energy levels to high energy levels. The mass spectrometer analyses the transmitted radiation relative to the incident radiation and an absorption spectrum is produced. Absorption spectra show colors with black lines and the black lines represent where the energy is absorbed.

Emission spectra result when a high voltage is applied to the gas. Emission spectra show black with a few colored lines. The colored lines are the same as those that are missing from the absorption spectrum. They read like bar codes to identify unknown elements. Mr. Anderson is on the case. SL can stop watching around 3 minutes in, but HL must watch the entire video. |

Let's play around with average atomic mass. Download this handout. We will have to make adjustments because clearly, we don't have M&Ms, Skittles or Reese's Pieces.

Mission 4: Electrons Acting a Fool.

Mission Objectives. You should be able to...

1. Explain why the shell models of the atom are incorrect.

2. Explain the four quantum numbers.

3. Draw orbital diagrams for elements 1 - 20.

4. Write electron configurations for elements 1 - 20.

5. Write abbreviated electron configurations for elements 1 - 20.

As you're learning about atomic theory and the development of the atom, you should discover that most of the models do not specify the arrangement of electrons. JJ Thomson acknowledged their existence, but his model left a lot to be desired in terms of arrangement. Rutherford's model showed the existence of a positively charged nucleus, but does not describe the behavior of the electrons we know existed at that time. Nagaoka's model is similar to Bohr's model in that the electrons orbit the positively charged nucleus, but Nagaoka's model couldn't explain what kept the electrons from falling into the nucleus. Bohr predicted that electrons orbit the nucleus in energy levels similar to how planets orbit the sun. Bohr's model works for hydrogen, but for successively higher atomic numbers, the model fails. The reason the model fails for other elements is because (1) it assumes that the positions of the electrons are fixed, (2) it assumes that energy levels are circular, and (3) it suggests an incorrect size scale for atoms.

Knowing these problems, a newer model for the atom was developed using mathematics and probability. This is due to the fact that there is a level of uncertainty in the location and behavior of electrons, so the previously designed "shell" model no longer works. Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle says that one cannot know the position and momentum of an electron simultaneously because measuring one quantity changes the other. This means electrons cannot be in set orbits as the previous models describe. They have to be in 3D regions of space called orbitals. Electrons also spin in two directions: positive (up) and negative (down). Therefore, only two electrons can exist in an orbital. This makes it impossible for eight electrons to be in one "shell."

As a result, the Quantum Mechanical Model, which is a mathematical model that is based on the probability of locating an electron, was developed and is the model we currently use today. It is postulated that 90% of the time, electrons can be found in these orbitals, and the behavior of electrons can be described using four quantum numbers: size (n), shape (l), orientation (ml), and spin (ms).

Mission Objectives. You should be able to...

1. Explain why the shell models of the atom are incorrect.

2. Explain the four quantum numbers.

3. Draw orbital diagrams for elements 1 - 20.

4. Write electron configurations for elements 1 - 20.

5. Write abbreviated electron configurations for elements 1 - 20.

As you're learning about atomic theory and the development of the atom, you should discover that most of the models do not specify the arrangement of electrons. JJ Thomson acknowledged their existence, but his model left a lot to be desired in terms of arrangement. Rutherford's model showed the existence of a positively charged nucleus, but does not describe the behavior of the electrons we know existed at that time. Nagaoka's model is similar to Bohr's model in that the electrons orbit the positively charged nucleus, but Nagaoka's model couldn't explain what kept the electrons from falling into the nucleus. Bohr predicted that electrons orbit the nucleus in energy levels similar to how planets orbit the sun. Bohr's model works for hydrogen, but for successively higher atomic numbers, the model fails. The reason the model fails for other elements is because (1) it assumes that the positions of the electrons are fixed, (2) it assumes that energy levels are circular, and (3) it suggests an incorrect size scale for atoms.

Knowing these problems, a newer model for the atom was developed using mathematics and probability. This is due to the fact that there is a level of uncertainty in the location and behavior of electrons, so the previously designed "shell" model no longer works. Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle says that one cannot know the position and momentum of an electron simultaneously because measuring one quantity changes the other. This means electrons cannot be in set orbits as the previous models describe. They have to be in 3D regions of space called orbitals. Electrons also spin in two directions: positive (up) and negative (down). Therefore, only two electrons can exist in an orbital. This makes it impossible for eight electrons to be in one "shell."

As a result, the Quantum Mechanical Model, which is a mathematical model that is based on the probability of locating an electron, was developed and is the model we currently use today. It is postulated that 90% of the time, electrons can be found in these orbitals, and the behavior of electrons can be described using four quantum numbers: size (n), shape (l), orientation (ml), and spin (ms).

We use the QMM to show how the electrons in an atom are arranged around the nucleus.

Electrons obey three rules in their arrangement. You can read about them here. As atomic number increases, electrons fill energy levels and sublevels in an orderly fashion. The simplest sublevel is "S." The above image shows the S sublevel on the left. The image on the right is the P sublevel. You can look up D and F sublevels. They're really funky-looking. As energy level increases, the size of the sublevel increases. Electrons in the outermost energy levels are called valence electrons. These electrons are the ones that determine chemical behavior.

Homework: Review the videos and take a look at this practice test. See if you can answer the questions. The test comes with an answer key so you can check your work. If there is a reason why you feel you can't answer a question, then that is a question you must ask me during class.

Homework: Review the videos and take a look at this practice test. See if you can answer the questions. The test comes with an answer key so you can check your work. If there is a reason why you feel you can't answer a question, then that is a question you must ask me during class.